Since his first voyage to Italy in 1963’s From Russia With Love, James Bond has travelled the length and breadth of Italy, from the ancient city of Rome to the wintry chills of Cortina d’Ampezzo and the sunnier climes of Sardinia and Matera. As well as providing scenic beauty and glamour, the Italian backdrops have amped 007’s drama from pursuits through the narrow canals of Venice and foot chases over the perilous roofs of Siena.

Venice

As seen in: From Russia with Love (1963), Moonraker (1979), Casino Royale (2006)

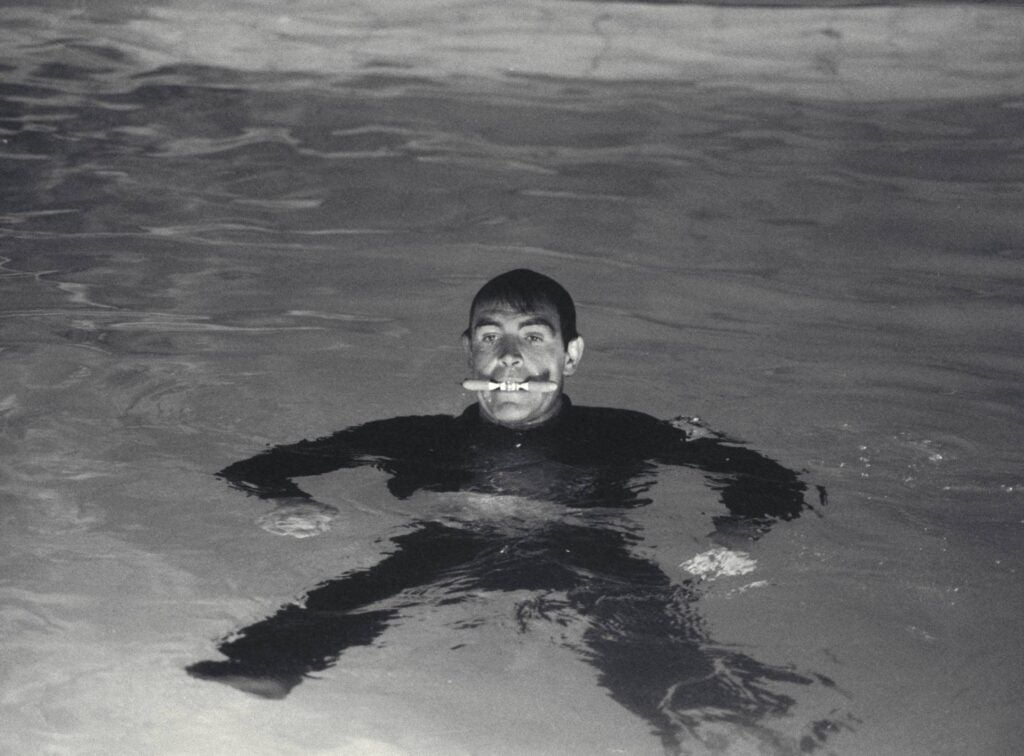

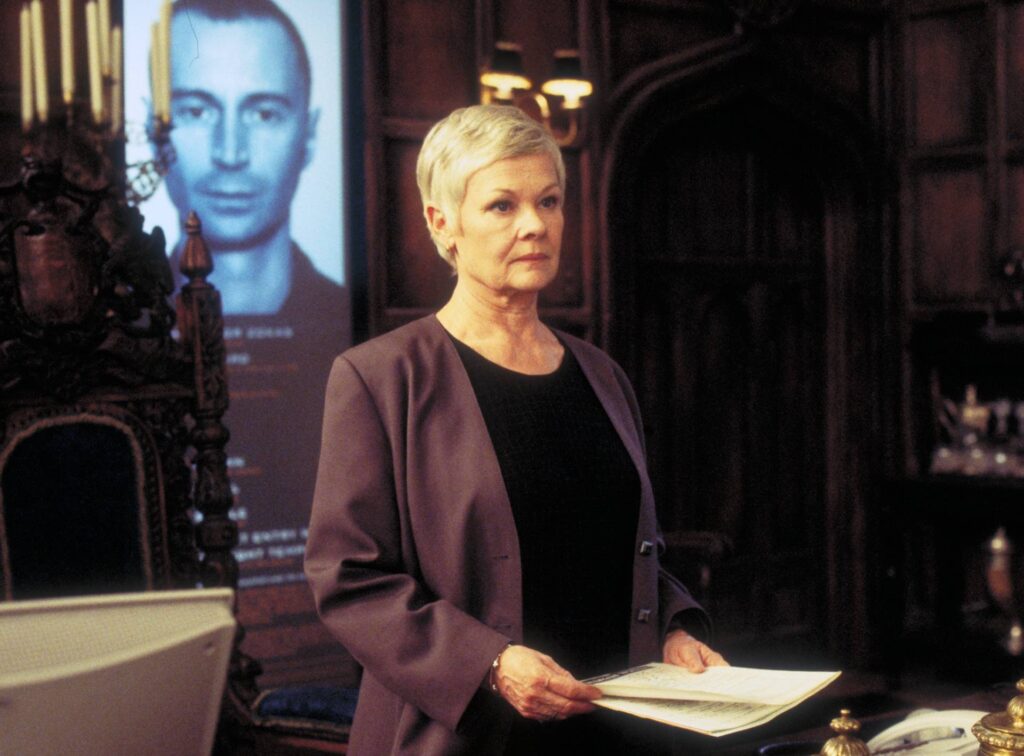

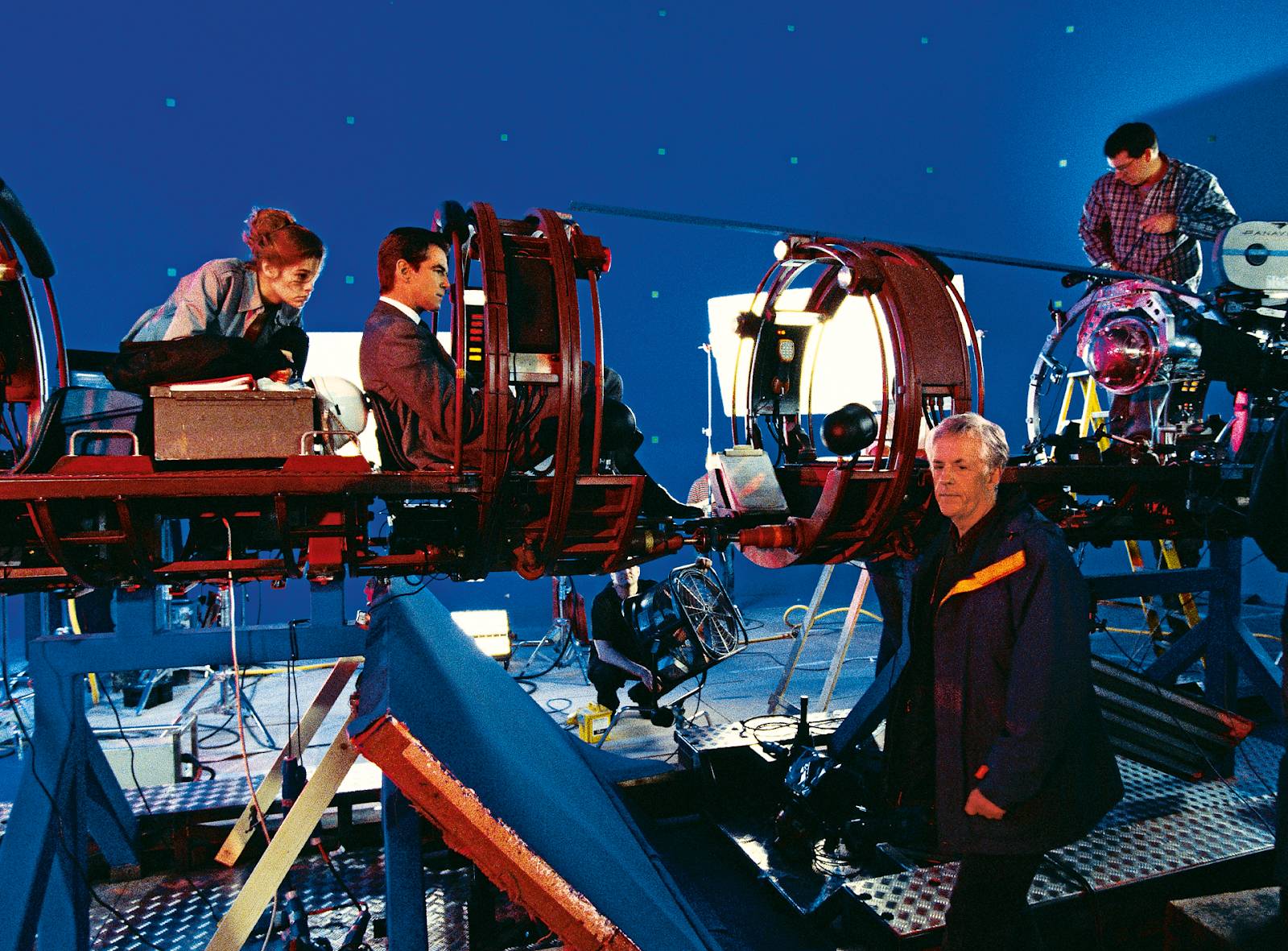

James Bond’s first of three forays to Venice appears at the end of From Russia With Love. 007 (Sean Connery) fights and kills SPECTRE agent Rosa Klebb (Lotte Lenya) in a hotel room with a view over San Giorgio Maggiore, Bond and Tatiana Romanova (Daniela Bianchi) later share a kiss in a water taxi under the iconic Bridge of Sighs. Director Terence Young and a film crew only spent a day in Venice. Connery and Bianchi performed their scenes against a back screen projection at Pinewood Studios in July 1963 while Piazzetta San Marco leading to Piazza San Marco was used as a backdrop for the film’s end credits.

Venice played a much bigger role in Moonraker. Bond (Roger Moore) is on the hunt for Hugo Drax (Michael Lonsdale) which takes him to the Venini Glass Works located at the Piazzetta dei Leoncini next to Saint Mark’s Basilica. Coming under attack on the canals by Drax’s assassins, Bond turns his gondola (nicknamed the Bondola by the crew) into a hovercraft and travels across St. Mark’s Square.

“I had to drive this 80-foot-long gondola across St. Mark’s Square, where there were thousands of tourists who didn’t know there was a film going on,” recalled Roger Moore. “I was absolutely petrified. I didn’t have that much control over it. They eventually gave me a little klaxon to warn people.”

Bond returned to Venice 27 years later with Casino Royale. Sending M his retirement notice, 007 (Daniel Craig) enters Venice on a luxury yacht with Vesper Lynd (Eva Green). Vesper double crosses Bond and a chase ensues through Piazza San Marco and various alleyways, leading to a battle inside a collapsing palazzo which was shot mostly at Pinewood. “Though it’s a wonderful city, it’s not the easiest to film in,” recalled director Martin Campbell, who had to shoot around hordes of tourists.

For the sequence of Bond and Vesper sailing up the Grand Canal on a 54ft (16 metre) yacht named Spirit, the vessel was sailed from England to Nassau, The Bahamas to film the scene with Bond and Vesper enjoying time together before setting sail for Venice. An aerial unit captured the yacht entering Venice, the first boat allowed to sail on the Grand Canal since it was prohibited for outside traffic 350 years ago. The mast was taken up and down to move under the bridges. “It’s not a bad way to earn a living, sailing a yacht up the Grand Canal,” said Daniel Craig. “The traffic jam we caused was terrible. I don’t know if they really do have tailbacks in Venice but they had tailbacks that day.”

Sardinia

As seen in: The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)

Bond (Roger Moore) and Soviet agent Anya Amasova (Barbara Bach) arrive in Costa Smeralda, Sardinia to infiltrate the operation of shipping tycoon Karl Stromberg (Curt Jürgens). The island in the Mediterranean plays host to a spectacular chase as 007’s Lotus Esprit is pursued by cars, a motorbike and helicopter. The only way for the camera to keep pace with the Lotus Esprit was to mount it in another Lotus Esprit.

Also shot in Sardinia was Bond’s journey to Stromberg’s aquatic base Atlantis on a wet bike. The prototype was built by Nelson Tyler with a 65 horsepower, two cycle engine capable of speeds of 50 miles per hour. “Nobody had ever seen one before,” recalled Roger Moore.

Cortina d’Ampezzo

As seen in: For Your Eyes Only (1981)

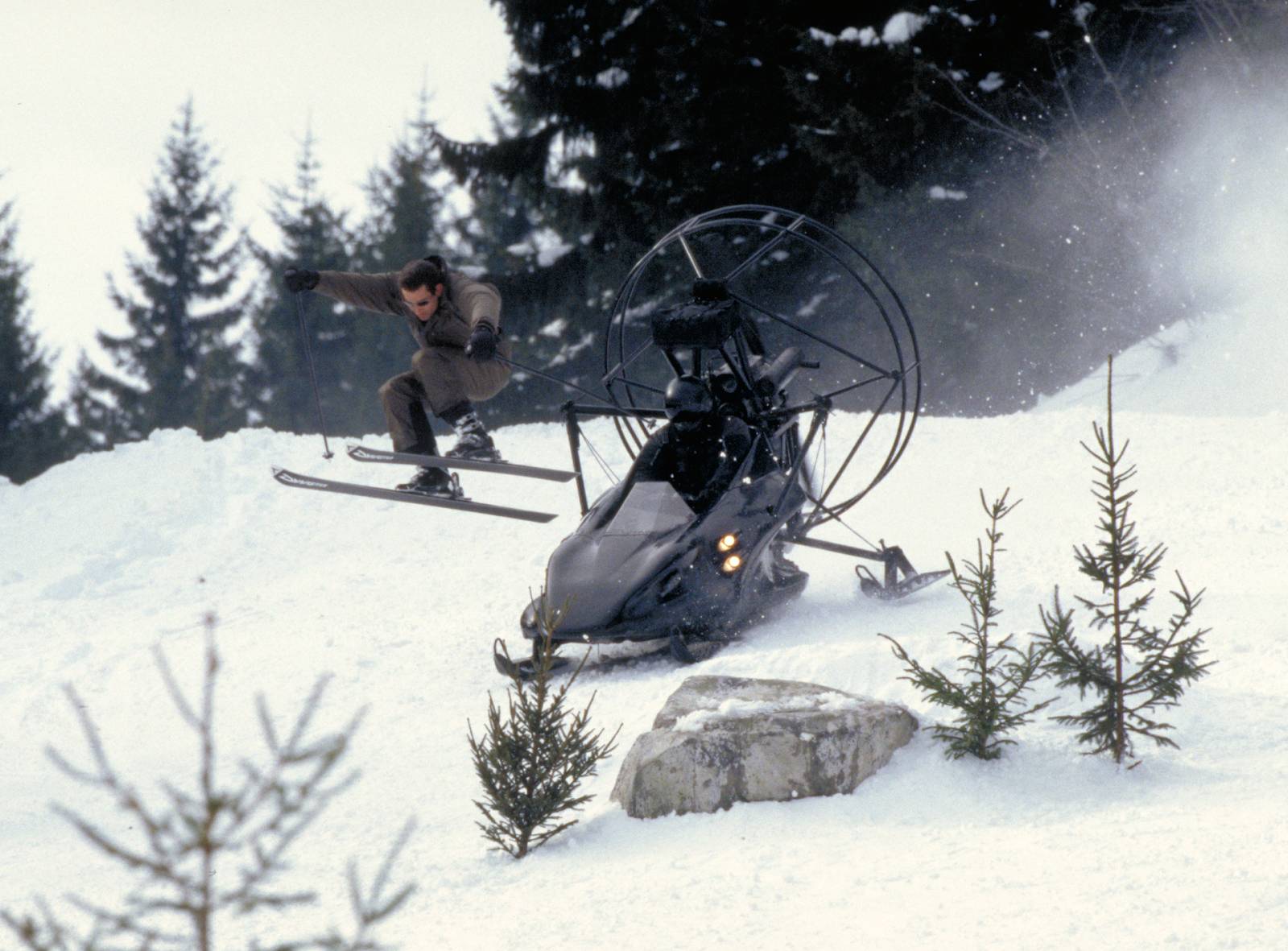

From the warmth of Sardinia, Bond’s next Italian sortie saw him enter the winter wonderland of Cortina d’Ampezzo, home of the 1956 Winter Olympics. Willy Bogner shot the ski sequences where Bond (Roger Moore) is chased down a mountain ending up in a pursuit down a bobsled run.

When the unit arrived in Cortina in January 1981, they were faced with multiple challenges. “Cortina was damn cold,” said Roger Moore. “It was January — but there wasn’t any snow in the village.”

“Overnight, Tom Pevsner and his men got a convoy of trucks that fetched snow in the mountains and dumped it in Cortina,” said Michael G. Wilson, then working as an assistant to his step-father, producer Cubby Broccoli. “When the people got up in the morning, the whole village was covered in snow.”

Lake Como

As seen in: Casino Royale (2006)

Lake Como appears twice in Daniel Craig’s first outing as Bond. The first, shot at the Villa del Balbianello near Lenno, sees 007 recuperating from torture at the hands of Le Chiffre (Mads Mikkelsen) and forge a deeper connection with Vesper.

“Lake Como is one of the most beautiful spots in the world,” said producer Michael G. Wilson. “This is where the love affair between Bond and Vesper begins.”

The second occurs when Bond tracks down and shoots Mr. White (Jesper Christensen) and Craig utters the line “The name’s Bond. James Bond” for the first time. The moment was filmed at the private residence Villa la Gaeta in Sant’Abbondio located near the resorts of San Siro and Menaggio.

Lake Garda & Carrara

As seen in: Quantum of Solace (2008)

The pre-credit car chase sequence between Bond’s Aston Martin DBS and Alfa Romeo 159s was captured in two distinct Italian locations: on the roads and tunnels around Lake Garda, then in Carrara for a pursuit through a quarry.

The sequence employed seven Aston Martins and eight Alfa Romeos. The tunnel chase was complicated by the tunnel only being 28 ft wide in parts. As stunt coordinator Gary Powell noted, “When there are over 40 cars going through it at the speeds we were doing, it becomes a technical challenge.” After ten days shooting at Lake Garda, the unit moved to Massa to take advantage of the Carrara marble quarry.

“Some of the mountain roads we were on were quite high up and very narrow,” remembered Powell. The quarry was 3,500ft above sea level and we had cars coming down, doing handbrake turns, going round corners at speed with a 750 ft drop next to them.”

Siena

As seen in: Quantum of Solace (2008)

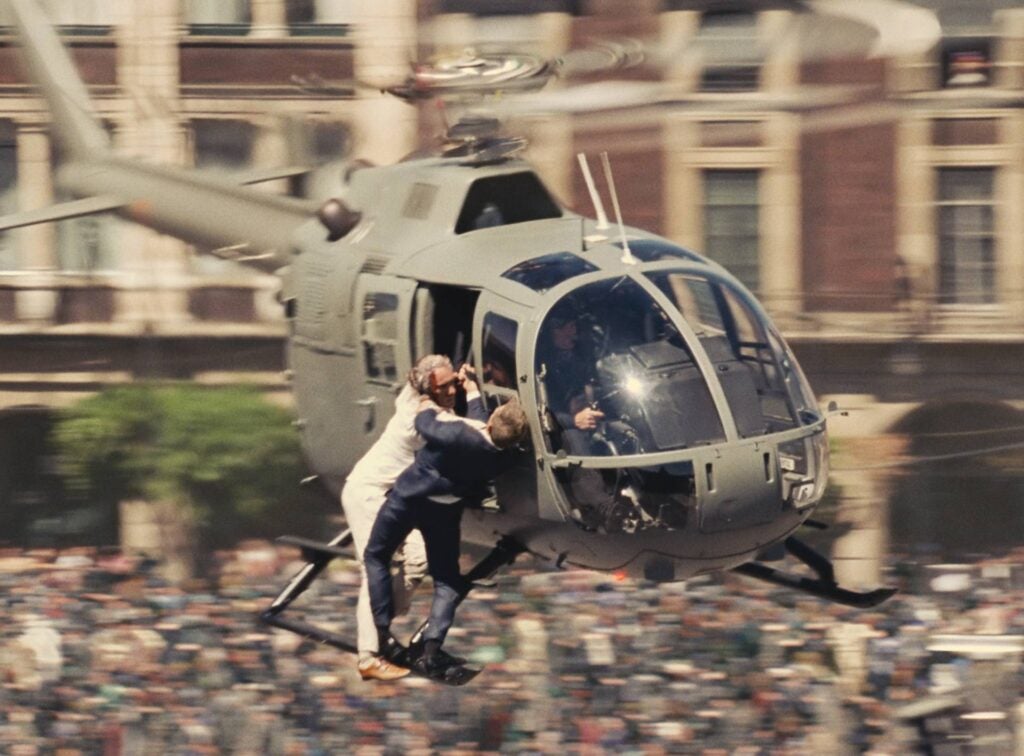

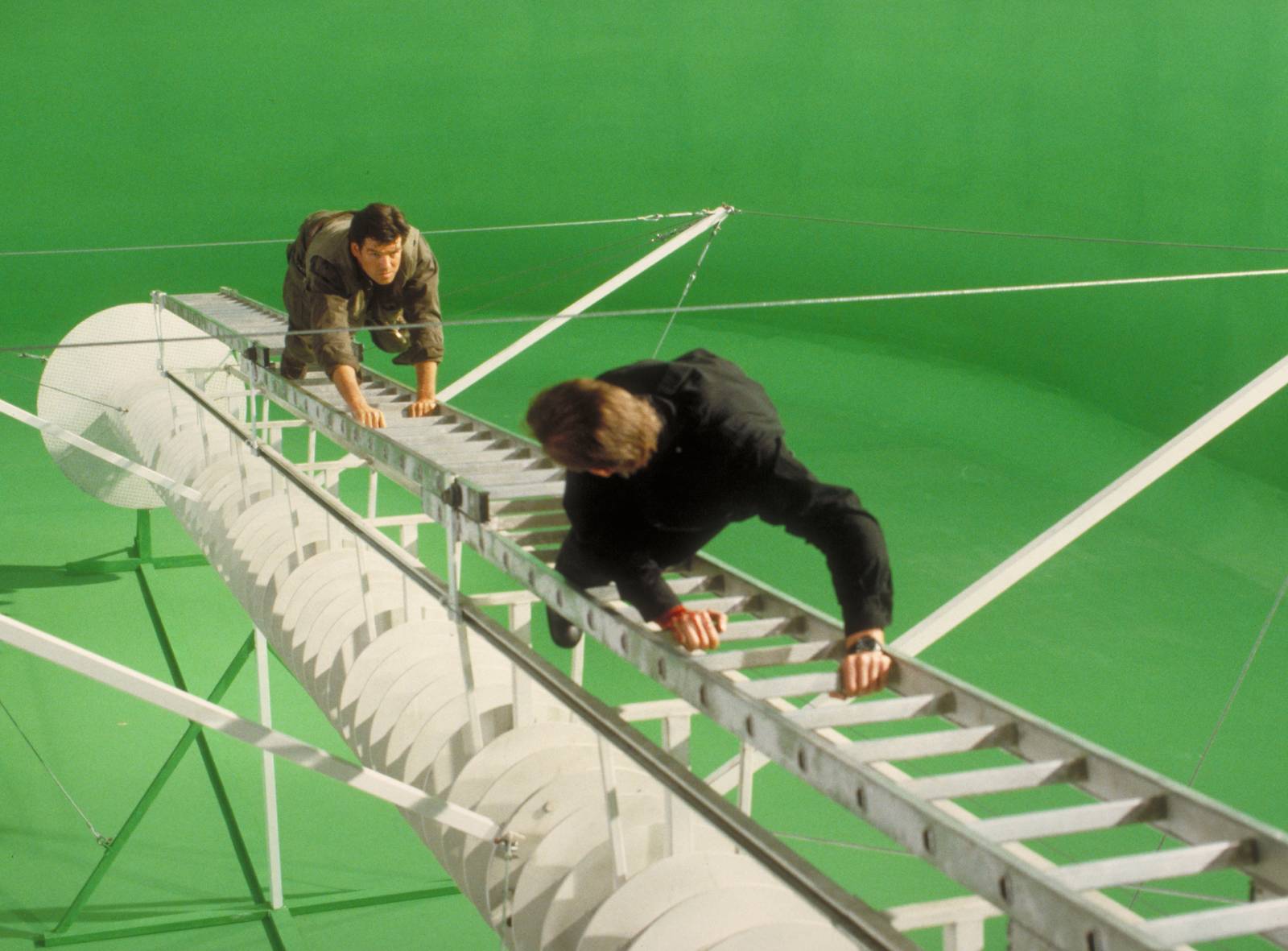

Following the car chase, Bond goes in pursuit of M’s double crossing bodyguard Mitchell (Glenn Forster) and gets caught up in the crowds watching the world famous Palio horse race at Piazza del Campo in the Tuscan city of Siena. As the race happens only once a year, the horse race had been captured months before principal photography began by a second unit crew.

“The Palio horse race is only about 90 seconds,” recalled First Assistant Director Michael Lerman. “We had ten camera crews shooting from rooftops, out of windows and on the track itself.” The chase continues over the picture-postcard Sienese rooftops.

While the initial idea had been to build the rooftops on the backlot at Pinewood, scheduling meant the team had to approach the Sienese City officials to take over the rooftops for a couple of months for filming. “I did a 25-foot jump,” Daniel Craig remembered. “It’s not that scary jumping off the side of a building with a wire on. I’d rehearsed the jump, so was mentally prepared, then they put a moving bus underneath and it suddenly becomes something else.”

Vatican City, Rome

As seen in: Spectre (2015)

Bond (Daniel Craig)’s sojourn to Rome is the series’ first visit to the Eternal City. The funeral of Marco Sciarra was staged at the Museum of Roman Civilisation. Also shot there were night exteriors for Lucia’s villa at Villa Di Fiorano and the Aston Martin DB10 speeding past the Coliseum.

The centre-piece is a duel between Bond’s Aston Martin DB10 and SPECTRE operative Hinx’s (Dave Bautista) Jaguar C-X75 through the cobbled streets and towpaths.

“We had two of the fastest cars in the world travelling at night at speed, through what is near enough a world heritage site,” said Executive Producer, Callum McDougal.

“Via Nomentana was one of the longest city lock-downs our location department had ever done. It was about 3 kilometres of main roads entering Rome,” recalled Associate Producer, Gregg Wilson. “This means that you are employing hundreds of blockers to make sure no people or vehicles wander into shot.”

A highlight of the chase sees the cars go down the Scala de Pinedo steps – which were reinforced for their own protection – and onto the towpath by the river Tiber, which just prior to filming had been prone to flooding. Shooting around such beautiful antiquity meant the filmmakers had to take precautions during production and adapt as necessary. The sequence ends with the Aston Martin flying into the water and Bond parachuting to safety at Ponte Sisto.

“We always try to do things on-screen that have never been done before, and the result in Rome was spectacular. It is something we feel very proud of, and I think the Romans will feel very proud as well,” said Barbara Broccoli during production.

Matera

As seen in: No Time to Die (2021)

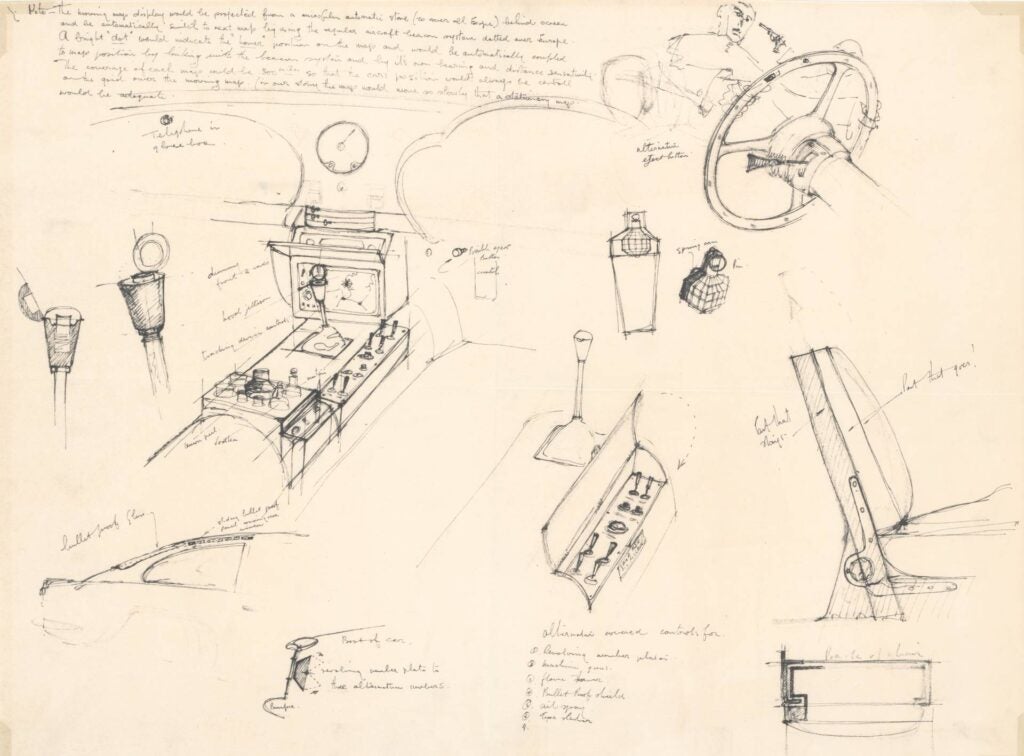

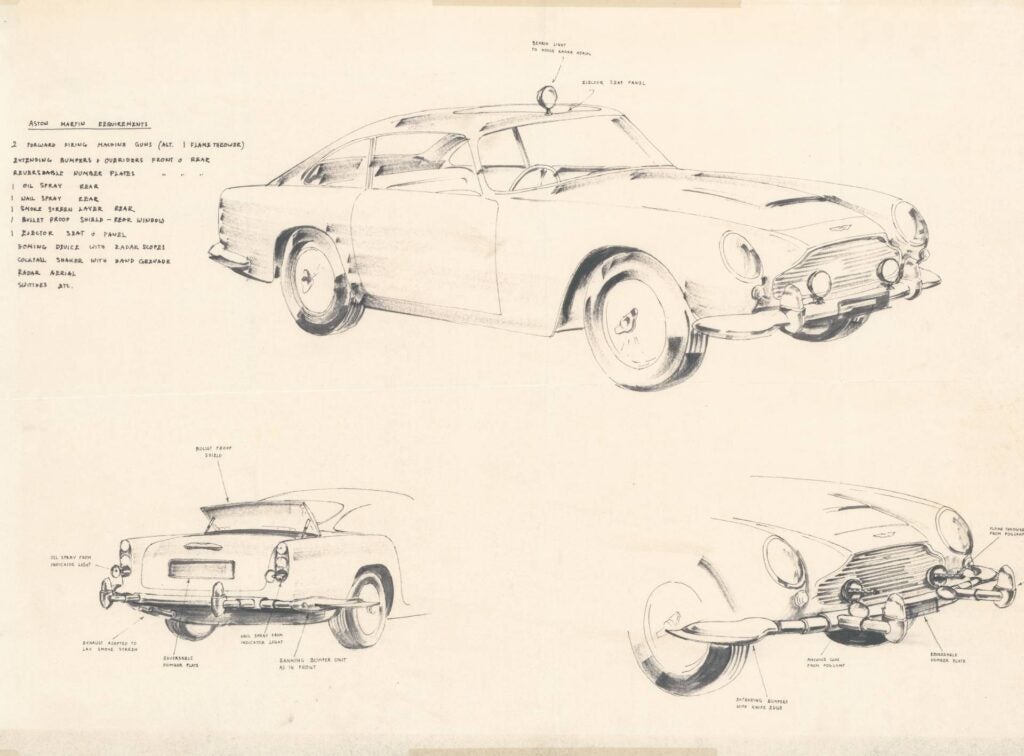

Bond 25’s pre-credit sequence sees 007 (Daniel Craig) and Madeleine Swann (Lea Seydoux) travel to the city of Matera in Southern Italy. The crew shipped ten DB5s, eight of which were built by Aston Martin and the special effects team. The other two were original 1964 DB5’s used in previous Bond films.

When SPECTRE agents surround 007 and Madeleine in the Piazza San Giovanna Batista, the DB5 has some tricks in its locker, firing bullets from its front lights and a smoke screen from the back as it spins round before peeling off. “Matera is tiered like an amphitheatre so whenever the DB5 did a stunt at the end we heard the locals hollering and giving us a round of applause,” recalled Special Effects Supervisor Chris Corbould.