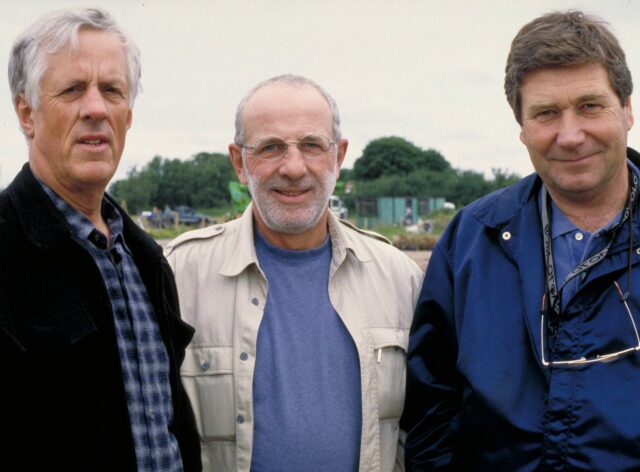

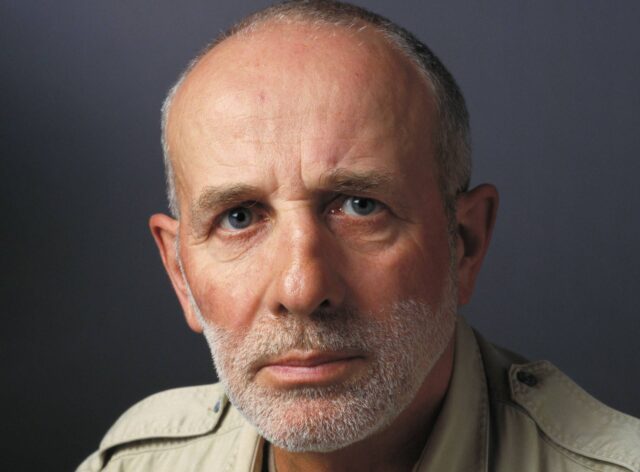

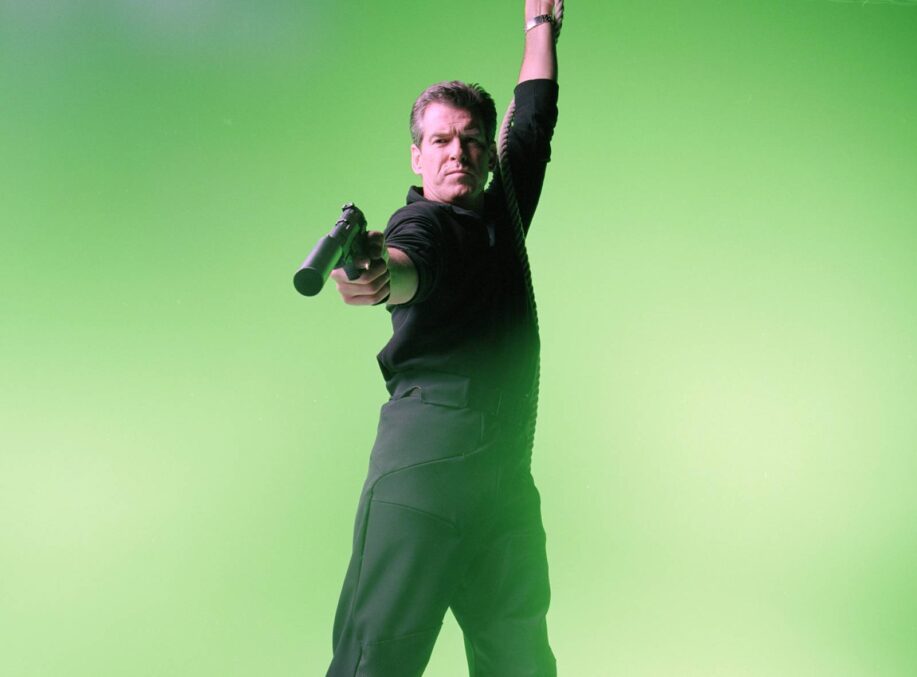

Movie Magic With John Richardson – Part 2

In conversation with the legendary special effects maestro

In part two of our conversation with Academy Award-winning special effects supervisor John Richardson, we discover how he created incredible explosions, futuristic gadgets and turned a cello case into a fast-moving getaway vehicle for James Bond.

There are a lot of special effects shots in A View to a Kill – how did you create the shot of the blimp going over the Golden Gate Bridge?

It’s a classic demonstration of model work. We had to build four different sizes of airships: a small one, 10 ft one, and 40 ft one. We built them so the bigger one could either hang under a crane to blow it up with air or we could fill it full of hydrogen and tether it from underneath. Whichever shot we were doing, it made it much easier to lose the wires. That was all part of the trickery of model work. CGI can paint wires out so much easier now but we had to be very inventive and every shot was a different model. We had a background of San Francisco, which was a photographic cut out, with real sky behind it which was in the bottom of frame. Everything above that was real with a model and the Pinewood backlot. We did similar things on The Living Daylights with a bridge that was supposed to be 200 ft high over a river. On the real location, it was six ft high over a muddy, dusty floor so we built a foreground miniature to make it possible.

Tell us about getting to the top of the Golden Gate Bridge?

I did all of the filming up on the bridge. The most interesting thing was getting up there! There was a lift that went up in the middle of the tower but the problem was the lift was very small. It was literally only big enough for three of us when crushed together and a seven minute journey. So you’re squeezed in the metal coffin in the middle of the bridge and we’ve got all the camera boxes in there with us too. On your way up you think, “What would happen if there was an earthquake now or if all the power went out?” One occasion we got to the top and we were so crushed that none of us could reach the door handle to open it to get out! That was fairly amusing for a few minutes.

What did you capture while on top of the bridge?

I shot all the background plates of San Francisco so that you could have the actors in front of them with smoke and mirrors on the Pinewood backlot. I shot all the live action stunt work and the helicopter shooting while we were there. To do a lot of the plates we had to go 100 ft down one of the main cables and set up a camera on the cable itself. Now the cables are at an angle, it was the crack of dawn when we were going up there and it was wet too. What you don’t realise is that even though it’s a four ft wide cable on the bridge, there’s still a hell of a gap down the side. So as you walk down the bridge, the cable is bouncing as the lorries go over the bridge. It was very scary!

You must need a head for heights for that?

I must admit I did spend one night lying in bed wondering whether it was going to take more courage to go out and walk down the cable on the bridge or go into the production office and say I couldn’t do it! I decided at the end of the day, it was easier to go up there and do the filming than let people down so I just got on with it. It’s only when you’re on terra firma you appreciate not everybody gets to do these things.

You’re briefly on screen in A View To A Kill aren’t you?

Yes, in Zorin’s office. I’m on the front page of a mock-up of People magazine when Roger Moore looks at a painting. There’s a big photo of Zorin on the cover and a small one of me in the top corner with a caption saying ‘A real-Life JR’. I have Jerry Juroe (EON’s former marketing director) to thank for that.

The next 007 film you worked on was The Living Daylights. What are some of your favourite memories from that film?

We had the famous royal visit towards the end of filming which was an unexpected highlight. We set up a thing in Q’s workshop where a rocket had to be fired out of a ghetto blaster to blow a dummy’s head off. So we’d rigged it up for Prince Charles, as he was back then, to fire the missile and explode the head. That was the fun part for me on the day and Charles was brilliant. He fired it right on cue.

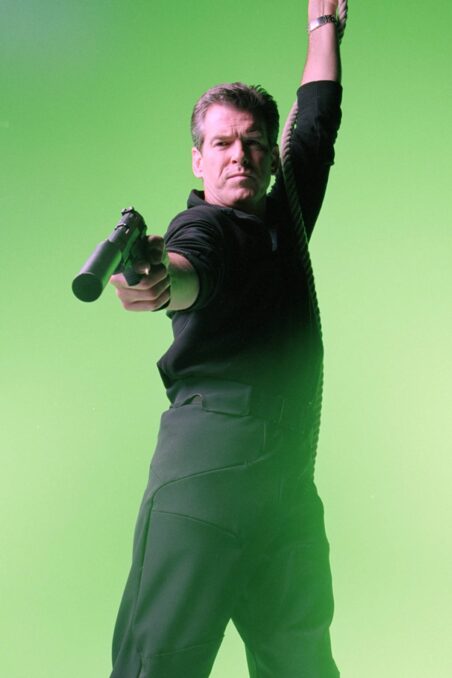

The Aston Martin V8 was laced with gadgets – was that your work?

It was fun to work with Aston Martin and have those cars around. We shot a lot of the scenes out in Weissensee in Austria. It was great because we had the Aston Martin V8 out on the ice and set off explosions. We had the skis out the side and tires that blew themselves up and let themselves down. There was an Aston Martin that we fired out of an air cannon to jump over the dam when a roadblock was in place. Just working on that lake was interesting. It was frozen over so we used to drive across it in the mornings to get to the location. It was quicker than going all the way around. But as you drive across, the ice would crack and break, and it made these extraordinary noises that echoed right across the lake with the cracks. It can be quite unnerving and was certainly an interesting place to shoot.

How did you prep the cello case for what was needed in the snow scenes?

We built the cello case. I built one for Timothy (Dalton) to steer. It had two steering handles so as he came down the hill he could safely steer it. Tim was great and up for anything. So he and Maryam d’Abo got on and went straight down the hill. They enjoyed it, it was great fun and worked perfectly. A funny thing happened when I went on to work onWillow afterwards. Another actor was supposed to get on a similar sledge we built out of a shield for him to ski down an easy snow slope in New Zealand. This actor turned up, looked at it and said, “I’m not getting on that thing and riding down the slope”. He said it was too dangerous and walked off. Then a young Warwick Davis saw it, got on and did the stunts and thought it was great. These stunts aren’t for everyone I guess. Tim was great at the physical side of the role and he wanted to take it more seriously and so didn’t have too many outlandish gadgets.

Do you actually have a favourite Bond scene?

They are all pretty unique so it is hard to pick a favourite. We sank a replica of Cubby Broccoli’s Rolls Royce in the gravel pit in Denham for A View to a Kill and that was quite fun. The V8 was the only Aston I was involved with that had to do anything unusual. We had the famous Land Rover vehicle which came out of the back of the Hercules plane with Tim and Maryam on and landed on a pallet. We shot it coming out of the back of the model aeroplane full speed with a long lens. It took 65 takes to get that in camera because you’ve got a model plane flying at probably 70 or 80 miles an hour, a cameraman on the long lens, a parachute pulling a vehicle out and you’re trying to get all of it in shot, with the desert and nothing else, all at the same time. Because you’re filming at five times normal speed, rushes just went on forever and used to drive everybody mad but we got some good takes in the end.

What are some of the other sequences you were involved in?

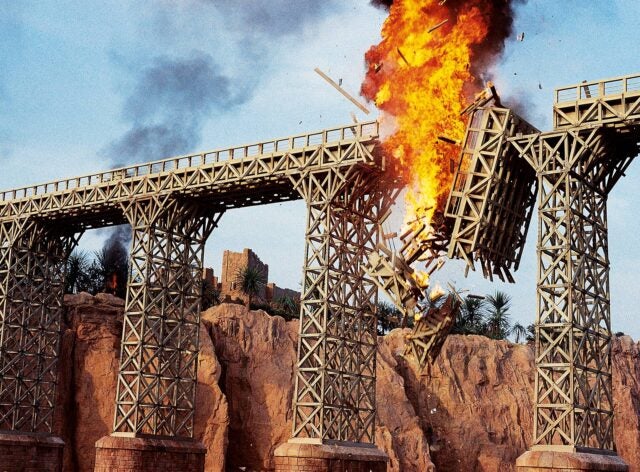

The Living Daylights had a vast array of different effects in it. The opening alone started out in Gibraltar for the chase sequence. We ended up having to fire a Land Rover off the top of Beachy Head with a dummy inside and a parachute coming out. We blew it up before it hit the sea. When we were doing that, we had the stunt guy coming off it with a parachute. Then for a sequence near the end of the film we built a lightweight Land Rover, travelled with it out to the Mojave Desert, took it up 10,000 ft under a helicopter and dropped it with the stunt man on top. So that was interesting. Apparently it made a wonderful noise when it hit the desert. I wasn’t there, I was up in the helicopter, but I can tell you it was as flat as a pancake! We also had all the stuff in Morocco, which was supposed to be Afghanistan, and the foreground miniature bridge, which was a real bridge but only 10 feet off the riverbed. So we built a foreground miniature to make it look 200 ft. Nobody who saw the film should realise that it was a miniature.

Is there any one moment that encapsulates your time on Bond?

There are so many! I’ve got wonderful stories from my time on the Bond films. I’ve included a story in my book about a model submarine that was bobbing along the ocean floor and towards a drop off of around 1,000 ft. The model was about to go barreling over the edge and down into the Pacific Ocean! That was scary. The prospect of having to phone Barbara Broccoli and say we couldn’t film anything as we’d lost the submarine was unthinkable. It made half a dozen guys get into their diving gear very quickly! But to answer your question, there are so many wonderful stories to tell. The question I’m asked all the time is, “What’s your favourite film” and it’s too hard to choose, every film is different. They’re fun for a myriad of different reasons. If you ask me what my favourite film is, then it would be all the Bond films.

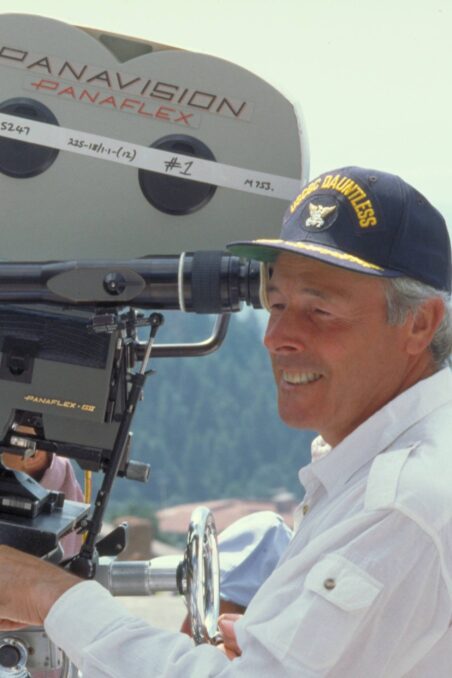

What makes working on the 007 films so special?

I mean, obviously with the Bond films what everybody echoes is that you’re part of the family. It’s the family working environment. Barbara’s lovely, Michael is lovely and Cubby was lovely. I have an old autograph book my father started for me in the 1930s which is filled with greats. Can I read you something from it? It’s from 20th April 1988, “Dear John, thank you for your magic, but mainly for your friendship, for all the 007 years. Fondly, Cubby Broccoli.” Now that is special to me. He was just such a lovely man and told great stories.

What is your favourite Bond film to actually watch?

I have two. I enjoy watching Moonraker because it brings back the whole experience of what I went through on the waterfall. But for a stand alone short sequence, the opening of Octopussy because it encompasses every piece of movie magic that you can pull together. I have nine Bond films on my CV and I remain incredibly proud of them all.

John Richardson’s books Making Movie Magic and Making Movie Magic – The Photographs are available from 007store.com.