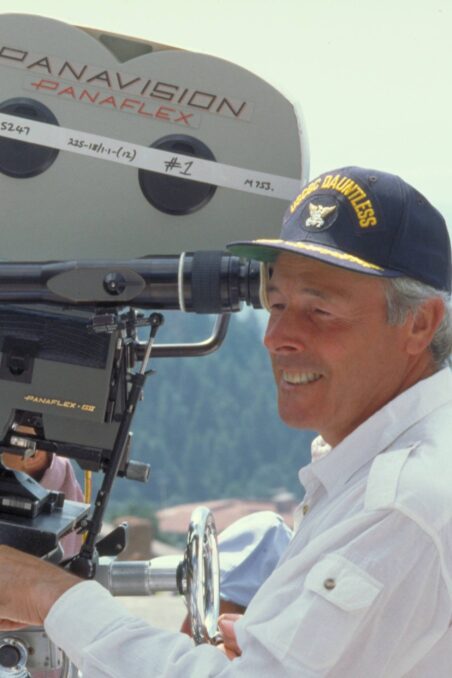

Movie Magic With John Richardson – Part 1

In conversation with the legendary special effects maestro

Though you might not know his name, you will definitely know John Richardson’s work – the pioneering special effects legend’s movie CV stretches back five action-and-adventure-packed decades. He’s been Oscar nominated six times (he won for Aliens in 1986) and his groundbreaking screen magic is seen in all eight Harry Potter films, Aliens, Superman, A Bridge Too Far, Straw Dogs, Rollerball, The Omen, Starship Troopers, Cliffhanger, Far and Away and Willow, amongst more than 100 films. Despite the extraordinary range and breadth of his movie experience, it’s still his nine James Bond adventures that have given John his most treasured movie memories. “I’ve been privileged to work with some of the Hollywood greats, a very wide swath of different technicians and actors on both sides of the camera,” he told 007.com when we sat down to discuss his extraordinary career, “but the Bond films have always remained closest to my heart.”

Why is it that the Bond films remain so special to you?

Who wouldn’t enjoy working on movies where you get to build huge sets, blow things up and also go to all the wonderful places where we filmed? We did really difficult and exciting things like filming 60 ft long model submarines 120 feet down off the Bahamas and flying model aircraft, building 40 foot long airships to do various things and conjure up different model scenes. Which I think to this day, is probably some of my proudest work – because I think many of the audiences when they were looking at the movies, didn’t even realise that they were models. So that, for me, has been one of the highlights, and to work with that sort of family atmosphere and receive their protection. It really was a family feeling and I am still in touch with people from the Bond family, which is lovely.

How did you get your film industry break?

Nepotism, very simply. My father was a special effects man and he started in the business in 1921. He worked on a lot of films with Cubby Broccoli and Irving Allen in the 1950s. Things like The Red Beret in 1953, High Flight in 1957 and Zarak in 1957. He also worked on Lawrence of Arabia and a whole bunch of movies throughout that era. I pretty much grew up on film sets. From the age of about 10 or 11 I used to go to work with him and learn the ropes during school holidays. I’ve worked on films like Exodus, Lawrence of Arabia, and then I left school in 1962. The first film I worked on was The Victors, which had a huge cast, directed by Carl Forman and then worked with my father for the next 10 or 15 years.

Your father was an industry legend – what was it like working with him?

A lot of people say it’s hard working with your father, and I suppose to a degree it is because if he’s gonna tell somebody off on a crew it is invariably his son, because it’s easier to do that than someone else. It was a great privilege to work with him though because he was the best. Certainly, throughout that era. He was very well respected, and was probably the most knowledgeable regarding the use of explosives. He was very safety conscious, had a great track record, so I was learning from the master and was very aware of it. He taught me well. He reached a point in his life where he wanted to slow down and retire and I started getting offers of films myself. Which was, I suppose, a little bit daunting.

What was the first film you supervised on your own?

The first film I supervised all the way through was Duffy with James Coburn, James Mason, James Fox and Susannah York, directed by a lovely director called Robert Parrish. I had to go out to the south of Spain and blow up a very big, real fishing boat. When I say blow it up, I mean, blow it up! We filmed it from a helicopter, which was challenging itself because I had to be able to fire it by remote control. Which, back in the 1960s, I think it was one of the first times radio control was used to do something on that scale. I was 21 years old and in charge of the effects on the movie. So by the time I was doing James Bond films I was still relatively young, in my thirties and forties.

You got your start in the Bond films with Moonraker – how did that come about?

I joined the Bond team on Moonraker which was an interesting and fun film to work on. The Bond team were struggling a bit with the volume of what they were doing. I’d worked with both the director Lewis Gilbert and Bill Cartlidge, the producer, before and they called me up and asked if I could go to Paris and talk to them. I did and I ended up taking over most of the filming in South America and all of the boat chase sequences in Florida. It sort of relieved the pressure on other team members like Derek Meddings. Derek was doing the model work on Moonraker. Johnny Evans was looking after the floor stuff in France and Italy. I got together with Derek and we talked it through and came to an agreement of how much I could take over because it was fairly late in the day to get everything prepared and shipped out to the location.

So for Moonraker, was it the boat chase you were tasked with creating?

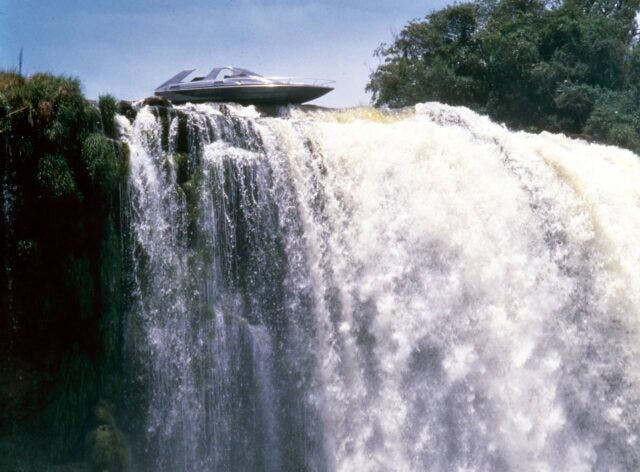

I took over the sequences that were going to be filmed in Iguazu and Florida, and it was mainly the boat chases and everything related to that. One of the things that happened was that they had recced the Iguazu Falls much earlier in the year. They’d looked at them when there was probably a lot less water going over the top. I went out there with the second unit director in November with a view to going back in January to film. They wanted to get Bond’s boat, which was a two tonne fibreglass speed boat, down in the river and right over the top of the waterfall, which was about a 360-foot drop. There was a vast amount of water coming down. It’s a huge river and I looked at it and said, “Personally I think the chances of it working because of all the rocks and everything out there is challenging. I’m quite happy to have a go if you want me to.” And then ended up with myself and one of my assistants, Johnny Morris, roped together going out about a quarter of a mile upstream of the edge of the falls. We’d have to walk, float, sink or swim or whatever from one rock to the next. I’d get to one rock and then I’d hold the rope to belay John while he swam over to join me. Then we pulled the boat across behind us and we did this all the way out. We got the boat down to about 100 feet short of the edge. It took us a whole day to get the boat out into that position and that was from first thing in the morning till late afternoon. Anyway, the next day, we set up all the cameras and got word over the radio to release the boat. We released the boat. It went thundering down in the water to the edge of the fall where it promptly impaled itself on a rock. Literally right on the edge of the fall with part of the boat sticking over the edge.

How on earth did you deal with that?

We went back to the hotel that night to have a meeting to decide what to do. The second unit director said, “Well, the boat can’t stay there. How are YOU going to move it?” I suggested that as I’d got a harness with me, we take the helicopter out which had a winch on it. They could lower me down onto the boat and the rock that it was stuck on and I’d see if I could push it or shove it over. We tried that and it didn’t work. We then figured out a plan: we tie a rope onto the cargo lifting winch under the helicopter and a rope onto my harness, as well as the winch, and they’d lower me down on the winch. Then they could hold me in place. Anyway, we flew out 30 feet underneath. Johnny, my sidekick, was in the helicopter signalling to the pilot and I think they dropped me in the water twice and in the bushes three times. Eventually, I got hold of the boat and signalled to John who told the pilot to stop flying. I suddenly heard a very strange ping-ping-ping-ping-ping noise over the sound of the helicopter. I couldn’t figure out what it was. It was quite loud. Then I realised it was the stitches on my harness breaking under the tension. I had two choices: do I stay with the boat or go with the helicopter? I figured there were probably more stitches left so I held on. I went with the helicopter and it took about 15 minutes to get me back up. As luck would have it, it rained up river overnight and a large torrent came and washed the boat over the falls in the middle of the night, never to be seen again.

That must’ve been terrifying?

I was scared stiff. I can’t say I enjoyed it in the moment. But I often thought about it after. I always raised it with the stunt teams that whatever they do, they get a bonus for doing it! But I suppose I can put it down to experience.

You returned to 007 with Octopussy. It features some all time great 007 sequences starting with the Acrostar “Bede” jet right as the film opens. That must’ve been an amazing film to work on?

I was on Octopussy from the beginning. The jet was in the script and it was flown by Corkey Fornof who had said that he could fly through a hangar which everybody was excited about. But of course, when it came down to the nitty gritty of how to shoot it, there couldn’t be anybody in or around the hangar at the time. I think we worked out that with the speed the jet was flying it would be in the hangar for less than half a second or something ridiculous. So filmically, it wasn’t gonna work. So John Glen asked what we could do. We came up with a foreground model and built a third scale Bede jet and a third scale hangar door that we set up in front of the real hangar at Northolt Airfield. We lined it up exactly with the hangar doors and it looked like the plane had flown into the hangar. Then we did the same thing at the other end for the plane leaving it.

Is it true you attached a real plane to a car to shoot the sequence?

I had this wonderful idea that we could get an old car, cut the top off it, paint it camouflage colours and add a steel polearm from the centre of the car with a gimbal on top with an air hydraulic system that would bank the real full size jet. We could bank it from side to side. So the idea was, I would drive it through the hangar at 75 miles per hour with stuntmen and people running hither and thither with some foreground dressing to help hide the car and stuntmen closing the doors at the far end to a stop which I think allowed me about six inches spare on either side. We did it about four times. I think literally 75 miles an hour was our speed. The last time we did it, I exited the hangar and the throttle on the Jaguar had jammed. One of my guys, Johnny Morris, was lying on the floor in the back of the car. So I got us outside on the tarmac at RAF Northolt where we were filming and we were in front of one of the Royal Air Force jet planes parked on the grass. It took me a few seconds to realise why the wretched thing wouldn’t slow down and of course it dawned on me then that it was the throttle. So I was able to switch the ignition off and steer the car onto the grass, I think much to the amusement of all the RAF guys. We ended up spinning across the grass until we finally came to a stop. It’s quite interesting to drive a Jaguar with a full size jet on top! That still remains one of my favourite sequences because it does encompass all the different sorts of types of visual effects.

Tell us about the knife throwing?

Some stunts were done for real by a guy called Barrie Winship and some by Tony and David Meyer who played the twins. The rest of the knife throwing scenes were created with wirework. Which is essentially where we had knives going down wires, including one in the forest scene that went in by Roger’s ear as he was pinned to the door. However, when they were doing the rotating disk knife throwing scenes in Octopussy’s circus you couldn’t put a wire on that because it was going round and round; the wire would get twisted. So we put flick-up knives built into the spinning disk. As it was going round, suddenly a knife would flick up through the disk. They pop up so quickly your eyes don’t catch it.

What are some of the other props and effects you worked on for Octopussy?

We had the three-wheeled Indian Tuk Tuk taxis that we souped up for all the chase scenes. We also had the rope in Q’s office which I tested myself and the wire inside broke and swiftly posited me on my arse from about 12 feet which was uncomfortable, but that’s why you test these things. We had cars on the railway lines, including a Mercedes being fired from an air cannon into the water. Some of the stuntmen thought that the car might hit them and jumped into the water. It didn’t though and landed perfectly, even gently nudging a boat. We created a yo-yo saw which really worked and we mounted one after filming and gave it to Cubby. For the lovers of poison pen letters we created a pen that dispensed acid, which was actually tartaric acid found in wine mixed with some bicarbonate of soda to give the fizz effect. There was also the blowing up of the hangar in the opening which required us to blow the thing sky high. It was great fun and I am lucky to have spent a lifetime in special effects.

In part two of our conversation with John he tells us about filming on the top of the Golden Gate Bridge, turning a cello case into an escape vehicle and a one-of-a-kind autograph from Cubby Broccoli. Read on 007.com next week.

John Richardson’s books Making Movie Magic and Making Movie Magic – The Photographs are available from 007store.com.