Bringing Bond’s Jamaican Retreat to Life

With Neal Callow, Mark Tildesley and Veronique Mallory

Art director Neal Callow, production designer Mark Tildesley and set decorator Veronique Mallory discuss how they created James Bond’s house in Jamaica, reflected the region’s history on screen and added unseen touches of Ian Fleming to a unique set featured in No Time To Die.

Where do you start to try and merge all the elements together for Bond’s Jamaican home?

Neal: With a film like No Time To Die, it all starts with the script. Taking the example of the Jamaica house, James Bond has retired from service from MI6 and he’s moved to Jamaica. He’s living this semi-retired life somewhere in a remote part of the north coast of Jamaica, so there’s your starting point. What is this guy like? For that, you can go back to what he was always like as a character through the Fleming books and the early films but you obviously modernise that, and then you think what would his house look like? What would he be doing in his house? Would he like to go sailing or fishing? He’s probably fixing up a few things around the place. He’s going to really want to blend in with the local population and have a bit of privacy to his world. Those conversations, we have with the production designer, Mark Tildesley. The set decorator is very important for that thing as well. Veronique Mallory was our set decorator and obviously the director who will have opinions of how to articulate that personality through environmental design. We’re looking at the legacy of the design of Bond films. We’re looking at the character and then we’re using all of those foundations to then sketch out what his house might look like in Jamaica.

Veronique, what was your approach when you’re dressing that set?

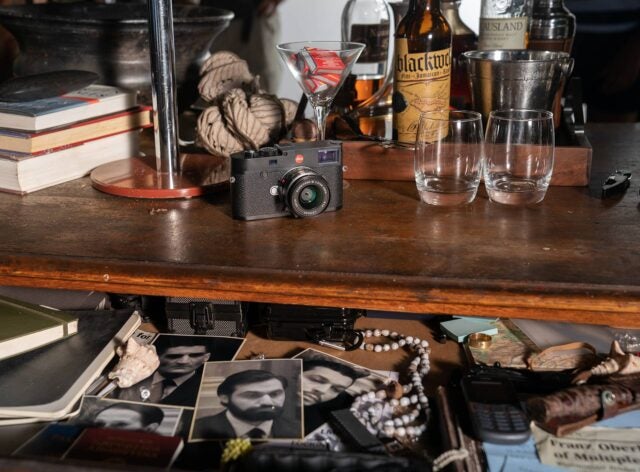

Veronique: We imagine the life of a gentleman who is reaching a certain age. We wanted to show the life of someone who has retreated from the active world but at the same time being into social interaction, interested in contemporary culture, very refined in his taste. As he’s a man who sails a lot and, like sailors in general, he likes handcrafted pieces of furniture and handcrafted objects, I tried to go along that way. I wanted to give James Bond and various surroundings this touch of old wood vintage choices that are mixed up with very contemporary objects. Every object for me was chosen by Bond because he is a man of great taste, he’s a man of intelligence and he wouldn’t live with some mainstream objects. I went looking for pieces that could be existing in a world but someone who would have been leaving the world and choosing another path for his life than staying in a big city. The objects chosen and the furniture chosen were some iconic designer pieces but not produced anymore. We recreate them and remake them because these pieces these days are museum pieces. You can’t have them and I tried to create an environment which was quite unique and original. They had to be very much touched beforehand by the hands of the workers, by the makers.

Mark, how important was it to go to Jamaica and have an authentic design for Bond’s home there?

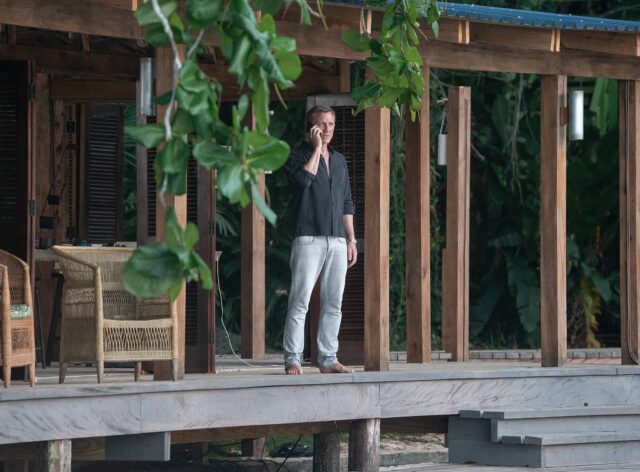

Mark: We went to Jamaica, which is the spiritual home of Bond movies and we find in the story of No Time To Die that Bond has retired there now. We were tasked with the idea that we would have to give him a home. “How do we make this glamorous?” A simple house won’t be glamorous but there’s something about the place where we built this house. It was just such a spectacular cove. I’m not suggesting that anything you put there would be wonderful but it was, in itself, a piece of beautiful nature. It’s really absolutely crystal clear waters and super tropical plants and wonderful sounds of birds and gorgeous skies. The task was to build him a house and we went through various forms of thinking about what that house could be. Should he have bought a house that already existed? Has he made it himself? Has he adapted a house that’s partly built? One of the things is that Bond is discombobulated there and sort of running out of ideas. He’s sort of a fish out of water. He’s really built to be an agent in action, and to be moping around on an island is not really his deal.

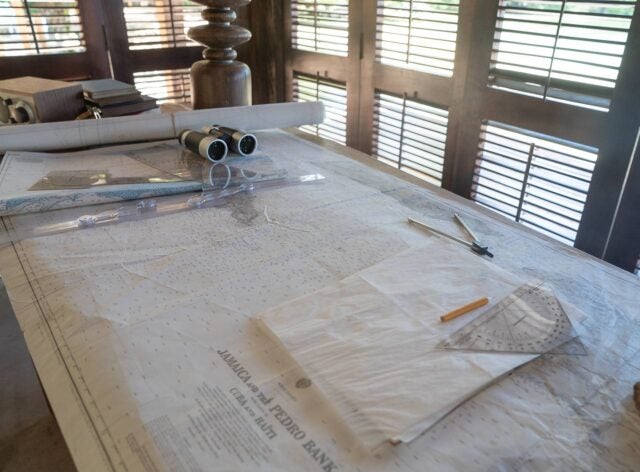

We built this house and it is very much a house by the sea, it’s about him getting in his boat and sailing away. Does a bit of fishing, does a bit of venturing and the only other things he’s doing in it, in terms of character based things, are he’s planning an escape. He has maps and books about where else he could test himself.

It really did feel like a place in Jamaica, it had a sense of location that it was grounded there. Was that something you were thinking about when you were bringing that together?

Veronique: Yes, it was, certainly. One of the main characteristics of that house was to have the sense of this Jamaica. Very laid back and very, very refined world in terms of fabrics, prints, woodwork. The house was built like that and what was dressed inside had the same kind of flavour.

Neal, the outside feels very local, and the inside feels like an amalgamation of the old and the new and also someone who’s got time so is that what you meant by things fixing up like the original?

Neal: Exactly. Veronique thought about all of those things so what we wanted to do there was to give the impression of an Englishman living in Jamaica for a start, so there’s things that would be recognisable as British set decorating or props lying around. The exterior of the house, and the construction methodology of the house, we wanted it to be Jamaican. We wanted it to look like a Jamaican built place but you’ll notice that there are certain aesthetic tweaks to it.

For example, there’s a big round window above one of the facades and that’s like a classic Bond design. It’s a piece of design iconography that we get these big, round shapes. Ken Adam was always about these simple, brutal shapes, creating amazing space, but not being particularly over complicated. We wanted to put something like that in there that gave a nod to Ken Adam but we wanted it to feel like it was a house that Bond hadn’t had built for himself. Bond had moved into that house and had been able to fix it up and do his own things to it and then he brought what little possessions that he has, over from whatever storage locker he has and put it around the house. That’s where you get those interesting choices of books, pictures, bits and other pieces. We see lots of Ken Adam classic set design in the film – Ken Adam uses a lot of that circular iconography, and it has become a classic design icon within Bond legacy production design. It’s always nice to get bits of that back in and we use that elsewhere in No Time To Die as well which again, if you look at that arrangement of sets, there’s a nod in there as well.

As we all know from James Bond, he’s an effortlessly stylish guy. So there’s certain kinds of furniture that he may have picked up locally, which are stylish but not too ostentatious or anything like that. Again, it all comes back really to thinking about what the character of Bond is. Production design for film in the end is about light. In fact, cinema is all about light in general so when we’re designing film sets, subconsciously or consciously, we’re designing for light and shadow. For a house like that one in Jamaica, we were very careful as to which way to orient the house in terms of the sun, the way the sun came up and the sunset at the end of each day. Obviously, all of those slatted doors on the side of Bond’s home, we had them made in a way that we could adjust the angle of the louvres in the door so that we could get the correct amount of light coming in or be able to shoot through them to the outside. So the whole thing, like most film sets, really is a lighting gobo which has been designed with the correct materials and the correct field tactility to tell the story of where we are. It is about designing for photography in the end and making everything look great on screen.

What are your favourite items and were any of them particularly tricky to get a hold of?

Veronique: In the living room, I especially like two or three of the chairs that were designed in the 60’s, in the 50’s by Italian or French or American designers like Lena Dubois who was an architect in Italy and created very interesting pieces of leather seats. We made one of those. A french designer also worked for creating houses in Africa, tropical houses. This atmosphere of tropic was there even within a piece of furniture and with the work of these amazing people.

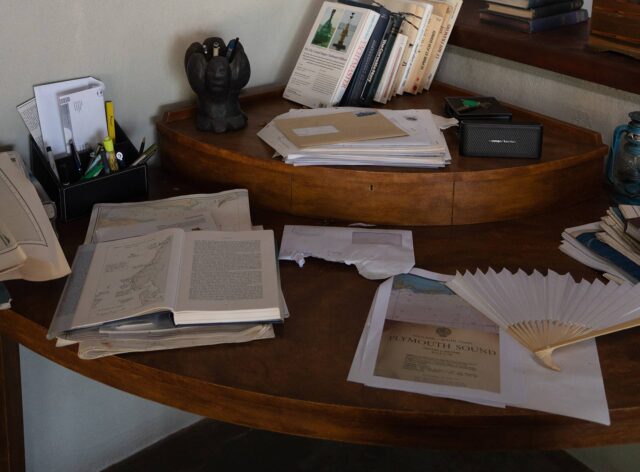

Of course, you’ve got the reproduction of the Fleming desk as well.

Neal: Fleming wrote the novels about James Bond in his home, GoldenEye, which is a few miles down the road from where we built the 007 house in No Time To Die. A lot of Fleming’s experience of his own life was obviously interwoven into the character of James Bond. We thought that was a really nice touch to be able to have the desk at which those books were written in James Bond’s bedroom because it connects Bond back to Fleming. Also, it has this aesthetic taste which Fleming himself might have had, which we would probably rightfully assume he would have given James Bond. Fleming was into lots of contemporary food and what would be considered exotic foods back in the day. Fleming’s own experience of what he would have chosen is interwoven into 007 so there’s a connection between the character of Bond and Fleming beyond that of just the fact that he wrote a character.

With the building of the house, how was it then that you approached the construction? Did you hire local crews to help create the Jamaican world for 007?

Neal: Well, it’s a combination of a few things, really. One is that we worked with an amazing construction manager called Steve Byrne who runs a company called Palette Scenery with his brother. He is an incredible guy and he also has a way of doing these jobs in foreign countries where he only hires local people to do it. So we had a carpenter, Benny Gillespie, and a painter called Nick. Other than that, everyone else was a local Jamaican worker and the way that Steve does this is he goes out early to the location that we’re proposing to build stuff at. He’ll go and spend his time going around meeting people asking: Does anyone know anyone who’s a carpenter, painter? Before we know it, he’ll have a team of people who are local to the area and are enthusiastic to do the job in their neighbourhood. He will do that on every job we go to. It’s an amazing kind of methodology. What that does for us, as a production, is it means that the people who are working on the film are engaged in it because it’s right in their backyard.

Mark, is it true there were access issues on the site?

Mark: Yes. We went from one bay to another looking for the perfect location. We finally honed down this one spot, which was spectacular, but there was no road into it and no possibility of a road, so the only way to bring anything to it was to take a boat, which we built a platform on and then we could move our wood and our materials round and build, physically, on the beach itself. No workshops or anything like that. It’s hand tools and these are the sort of things that I think are great. There are no wood yards as such. If you want wood, you go to a man that cuts down a tree, sadly, but nevertheless, that’s how they do it. They go up into the woods, cut down the trees and then bring back the wood. All the wood was very fresh and very new and very twisted. All our ideas about making this very sharp looking house disappeared and it became very Jamaican, very quickly, just by the nature of the people building it, the way we had to build it and the materials. It was a Jamaican built house.

We didn’t have much UK construction at all, we just had two people and a team of about 30 locals who were not film people. They are local joiners and carpenters and local house painters so this flavour of being handmade in Jamaica wasn’t very difficult to achieve because we had all the right people doing it.

We saw some wonderful works of art and lovely nautical maps. Could you tell us about those two things and how that ties in with his character?

Veronique: Well, the nautical maps were quite obvious. It seems that for someone who is travelling the world, travelling a lot and who likes the ocean, it was quite obvious to have maps. These nautical maps were something that you would naturally have around you. Not only because they are useful, but also because they’re very beautiful. They are beautiful artworks if you want to look at them precisely. Daniel Craig asked for some contemporary photos from artists. We looked for different kinds of prints and we had a chance to work with a Canadian photographer who agreed to use some of his work.

Did Daniel Craig have any input on any other aspects of the design of the home?

Mark: Daniel was fantastically supportive of all of our work and anything that was really pertinent to him like, for instance, that house. We obviously pitched that to him and carefully involved him in the process. As an actor, if you’re going to go and profess that this has been your house for the last 10 years and the first day you ever saw it is the first day of filming, it’s not a great thing in terms of feeling that you’re involved in the process. Daniel had some great comments, he’s a super supportive actor and we got in to tune quite quickly and understood where he was coming from.

Veronique: It’s really important though for Daniel to be involved. It’s the first time where we see a house in which Bond lives outside London. Until now we see places where, in general, he’s passing through and this one is his world. So it was extremely important for Daniel Craig’s character to keep an eye on everything that was in the house and to give his input and what it should look like.

What would fans be surprised to hear went into the production of the house that they might not have seen or heard of before?

Neal: Well, there was a challenging swimming pool in the middle of that set, which was this little sort of tide pool at the bottom of a waterfall that we always sort of wanted to be full but that was very, very difficult to fill up because the wall that was containing it was built 30 years ago and was leaking all over the place. We were doing everything we possibly could to try and plug the holes in this wall so that there would actually be some water in there for those nights scenes. But we finally managed to do it. I think it basically filled up, we shot it and it drained out again the next day so got very lucky with that. I mean, there was lots of stuff in that house. You know, there was so much created, like on all film sets really. So you’ve got to get everything ready. A set like that was pretty much a 360 degree set. You have limited information on what the DP is going to film and in which way they will want to set up the cameras. So there’s lots of the house that you didn’t see especially in the reverse of the exteriors, behind the house looking out to the sea, Bond’s workshop, all of that stuff. There’s lots of kinds of landscaping done. But I think in the end it it works well because we got the feeling of the place that we designed across, which is in the end that is our job is to create this environment in which the characters can tell their story and if the audience get the idea and you get the flavour of that world they live in then you’ve got get the message of what we were trying to do in terms of design. Then it feels like we have been successful and I think in this case, with Bond’s Jamaican Home, everyone could see what we wanted and it looked great on screen.